Water Treatment

Finding and maintaining a clean

water supply for drinking and other uses has been a constant

challenge throughout human history.

Finding and maintaining a clean

water supply for drinking and other uses has been a constant

challenge throughout human history.

Today, significant technological developments in water treatment, including monitoring and assessment, help ensure a drinking water supply of high quality in California and the West.

The source of water and its initial condition prior to being treated usually determines the water treatment process. [See also Water Recycling.]

Californians get their drinking water from Sierra Nevada streams, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the Colorado River and local sources, including groundwater. In a typical year, groundwater supplies 40 percent of the state’s total water; in a drought year, it can be closer to 60 percent.

Whether drinking water comes from surface water sources — including rivers, lakes and runoff from melting snow — or from groundwater drawn from aquifers, it has the potential for some level of contamination. Water treatment ensures that contamination is removed before the water is sent to homes and businesses.

COVID-19 UPDATE: California’s safe drinking water standards require a multistep treatment process that includes filtration and disinfection. This process removes and kills viruses, including coronaviruses such as COVID-19, as well as bacteria and other pathogens. California’s State Water Resources Control Board has more information here.

In general, surface water treatment problems involve more microbial types of contamination, or suspected carcinogens produced by the standard chlorine disinfection process.

Groundwater problems often are related to naturally occurring contaminants, or to seepage into an aquifer of chemicals from industrial manufacturing, septic tanks or farming.

Water Treatment Challenges

Water treatment technology must deal with a number of potential perils resulting from the movement of water from its source to tap.

These contaminants can include naturally occurring sulfur, zinc, or arsenic-laden formations. Groundwater can pick up contamination from fertilizers, septic tanks, mine drainage, or naturally occurring minerals. Rivers and streams sometimes carry harmful microorganisms from animals or humans, presenting a risk of disease. Storm drains can carry polluted runoff from cities into rivers and streams.

Pollutants and contaminants also can enter the water from farm drainage and sewage treatment plants. Other potential sources of pollution include landfills where rainwater can soak into the ground and leach harmful substances into groundwater. In homes, factories and buildings, corrosive water can dissolve lead in water pipes installed before 1986.

Some pollutants increase the turbidity of the water. Turbidity, or clarity of water, once was considered chiefly an aesthetic consideration, but it is now more closely observed because particles suspended in water can shield disease-causing microorganisms.

Recent attention has been focused on constituents of emerging concern (CECs) — a vast number of chemicals that are generally unregulated and include personal care products, pharmaceuticals, flame retardants and pesticides. Among the CECs are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) — a large group of manufactured substances that do not occur naturally and are resistant to heat, water and oil. Once in groundwater, PFAS are easily transported over large distances and can contaminate drinking wells.

Conventional water treatment techniques are ineffective for reducing PFAS levels in drinking water, according to the State Water Resources Control Board. Promising treatment techniques include granular activated carbon, powdered activated carbon, high pressure membranes and ion exchange resin.

Researchers and health officials also have struggled with the concern that the disinfectants—mainly chlorine— used in the treatment process to kill microorganisms can produce chemical disinfection byproducts. These byproducts are suspected carcinogens, chemicals that cause cancer.

To reduce the risk of cancer, water suppliers will be required to produce smaller and smaller amounts of disinfection byproducts or use alternative disinfection methods.

Water Treatment Regulation

Federal and state laws regulate drinking water in the United States, which generally ranks among the highest in quality globally.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency oversees drinking water quality for the nation, while in California, the State Water Resources Control Board’s Division of Drinking Water oversees state drinking water laws.

Of the more than 55,000 community water systems in the United States, only a small percentage annually report violations of one or more health standards, according to the EPA. Drinking water systems nationwide have spent hundreds of billions of dollars to construct water treatment and distribution systems and spend billions more for annual operation and maintenance.

Even so, more than 84 percent of all drinking water systems report having at least one potential source of contamination within two miles of their water intake or well. Officials say that a significant and overarching hurdle to overcome is the often-fragmented coordination among the various local, state and federal entities in charge of drinking water. Partnerships across jurisdictional, governmental and ownership lines are crucial to any community wishing to prevent contamination of source water, according to the EPA.

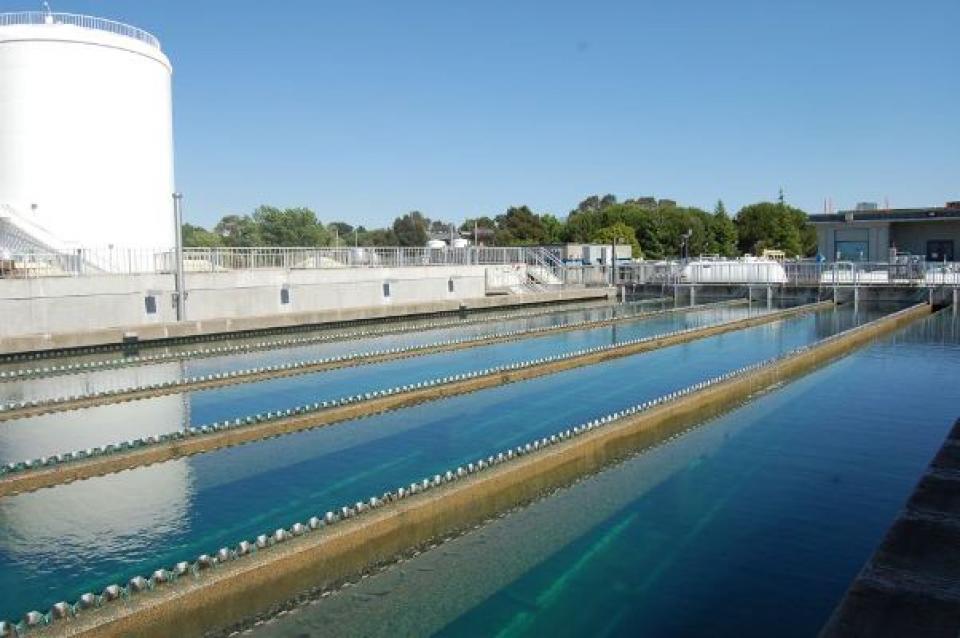

Watch a video here to see the inner workings of a water treatment plant along the American River that is owned by the City of Sacramento.