Bruce Babbitt Urges Creation of Bay-Delta Compact as Way to End ‘Culture of Conflict’ in California’s Key Water Hub

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: Former Interior secretary says Colorado River Compact is a model for achieving peace and addressing environmental and water needs in the Delta

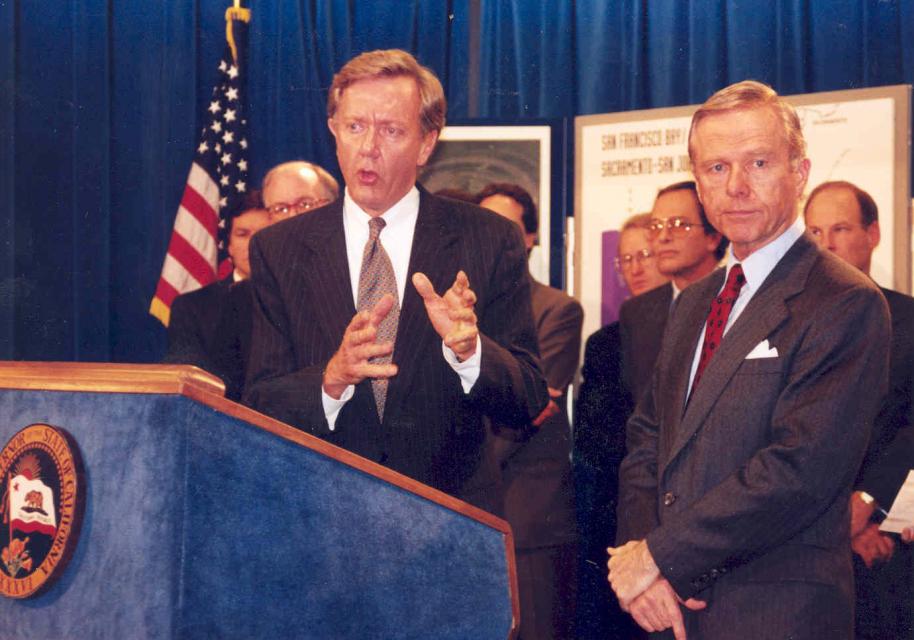

Bruce Babbitt, the former Arizona

governor and secretary of the Interior, has been a thoughtful,

provocative and sometimes forceful voice in some of the most

high-profile water conflicts over the last 40 years, including

groundwater management in Arizona and the reduction of

California’s take of the Colorado River. In 2016, former

California Gov. Jerry Brown named Babbitt as a special adviser to

work on matters relating to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and

the Delta tunnels plan.

Bruce Babbitt, the former Arizona

governor and secretary of the Interior, has been a thoughtful,

provocative and sometimes forceful voice in some of the most

high-profile water conflicts over the last 40 years, including

groundwater management in Arizona and the reduction of

California’s take of the Colorado River. In 2016, former

California Gov. Jerry Brown named Babbitt as a special adviser to

work on matters relating to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and

the Delta tunnels plan.

When Babbitt, 80, speaks, people take notice, and he didn’t disappoint before a packed house at the annual Anne J. Schneider Lecture April 3 in Sacramento. For more than an hour, he touched upon some of California’s thorniest water issues, such as the voluntary settlement process for flows into the Delta from the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers (which he’s helped negotiate) and the emerging tension between the Trump administration and California on water.

“We deal with the Bay-Delta piecemeal, one issue at a time. We work in stovepipes and promote endless conflicts.”

~Bruce Babbitt, former Arizona governor and Secretary of the Interior

But the man who helped negotiate the 1994 Bay-Delta Accord — which never quite achieved its lofty goals for Delta water management — suggested that a new course of action is needed, one that emulates the long-standing pact among Colorado River water users that has endured since 1922.

“We should now talk seriously about a California Bay-Delta Compact,” he said.

Analogous to the interstate agreement that exists among the seven Colorado River Basin states and Mexico, Babbitt said a conceptual Bay-Delta Compact would be a comprehensive effort highlighted by a stakeholder-drafted framework for how the Delta should be governed in the future.

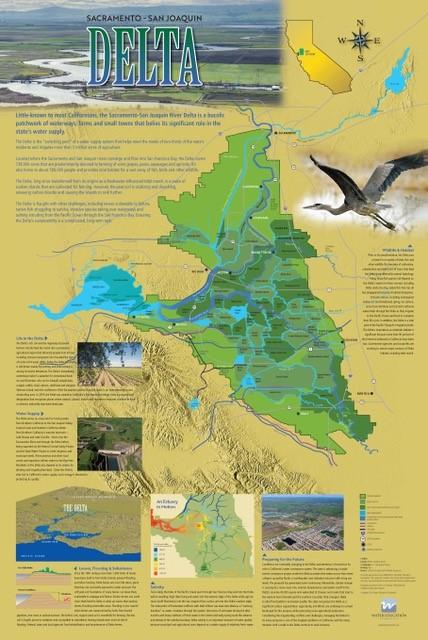

The Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta is a signature geographical feature in California, the hub of a water supply system that provides a portion of the drinking water supply for more than 27 million people. The largest estuary on the West Coast, the Delta relies on sufficient water flows to ensure a healthy ecosystem while also providing water to irrigate more than 3 million acres of agriculture.

A Culture of Perpetual Conflict

Babbitt, who enforced the federal Endangered Species Act for eight years at Interior during the Clinton administration, chided the Trump administration for failing to work with California on a balanced plan for water supply and ecosystem health in the Delta.

“A multispecies analysis of the

ecological needs of the Delta can be put together, but the

federal government has chosen to take an adversarial position,”

he said.

“A multispecies analysis of the

ecological needs of the Delta can be put together, but the

federal government has chosen to take an adversarial position,”

he said.

The Delta suffers because multiple agencies and interest groups have created a culture of perpetual conflict that has resulted in a dysfunctional process, Babbitt said. A significant source of the problem is the dominant sway of single-issue management that often gets tangled in controversy.

“The underlying problem is that we deal with the Bay-Delta piecemeal, one issue at a time,” he said. “We work in stovepipes and promote endless conflicts.”

A Bay-Delta Compact would begin through legislative authorization that would segue to an appointed commission of experts that primarily considers where the public interest lies in making the big decisions about water management. Its findings would be sent to the Legislature for an up or down vote.

Whether a compact could be negotiated between long-adversarial Delta water interests is an open question, given the legacy of conflict in the region. Indeed, it took legislative action to enact such significant laws as the Delta Reform Act of 2009 and the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014.

“Secretary Babbitt’s idea for an intrastate compact among warring water districts is audacious in its ambition, but given the history, I’m not sure it works,” said Alf Brandt, senior counsel to Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon and a veteran of California water law and policy, who attended Babbitt’s talk.

Lester Snow, former director of the

California Department of Water Resources who also attended the

talk, said Babbitt was attempting to lay out a different way of

looking at the system in a manner that gets all the issues on the

table for the development of a “grand plan.”

Lester Snow, former director of the

California Department of Water Resources who also attended the

talk, said Babbitt was attempting to lay out a different way of

looking at the system in a manner that gets all the issues on the

table for the development of a “grand plan.”

“In nearly 40 years, we haven’t been able to address the Delta issues and the habitat and the balancing, so why not [a compact]?” he said.

Babbitt acknowledged that a compact would not take anybody’s water away, but perhaps be more in sync with the concept of an environmental water right that has been broached by the Public Policy Institute of California and others. There is also the benefit of flexibility that comes with contracted water deliveries that vary annually.

“The premise is not to rewrite the law of water rights in the way they are vested in different users. I’m not that radical,” he said. But “there is a huge chunk of water allocated through contracts that has a lot of flexibility.”

“Secretary Babbitt’s idea for an intrastate compact among warring water districts is audacious in its ambition, but given the history, I’m not sure it works.”

~Alf Brandt, a veteran of California water law and policy

Furthermore, the basis of a compact must emerge from the ground up. “I’d be really careful about geographic allocation, instead reach for a kind of broad notion about a relative balance,” he said.

Beyond any possible strides toward achieving greater balance in the system, Babbitt suggested that a compact could be a bulwark against the Trump administration’s bid to increase Delta exports to users in the San Joaquin Valley and the raising of Shasta Dam.

“If California could come up with a compact, I guarantee you that federal regulation would back off,” he said. “It wouldn’t disappear, but it would have to take account of a framework statement by the sovereign state of California that this is the lens through which we view the resource.”

A unified vision for a compact framework is needed because of things such as the reconsultation between the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on the operation of the federal Central Valley Project. Designed to ensure the protection of endangered species, reconsultation has morphed into “a political process that lacks integrity,” with scientists under pressure to produce findings that justify increased water deliveries, Babbitt said.

“In nearly 40 years, we haven’t been able to address the Delta issues and the habitat and the balancing, so why not [a compact]?”

~Lester Snow, former director of the California Department of Water Resources

Noting that the Delta smelt are on the verge of becoming “functionally extinct,” Babbitt said the Fish and Wildlife Service has been “nowhere to be found in this process.”

Meanwhile, the drive to add storage through a raised Shasta Dam and the construction of Sites Reservoir, an off-stream storage facility about 70 miles northwest of Sacramento, has been conducted through a singular analysis without enough consideration of when and how water is delivered to farms, urban areas and the environment.

“Shasta is particularly troubling because the federal government is taking on a fight with the state of California,” Babbitt said. “There may be a very good case for raising Shasta Dam, but the federal government, at the instigation of the political direction of the administration, is saying, ‘We are going to do Shasta and we are going to run over California.’”

Likewise, while there may be a compelling case for Sites Reservoir, its water allocation impacts on all sectors haven’t been clearly stated. “We are basically saying ‘we will worry about [that] after the fact,’” Babbitt said.

Emerging Ideas From the Ground Up

The State Water Resources Control Board’s decision in December to set a 40 percent flow standard for three tributaries that flow into the lower San Joaquin River sparked an outcry among agricultural and municipal users that has reached the halls of Congress.

Babbitt, who was called upon to help

hammer out the voluntary settlement process designed to provide

water users with a soft landing, said while progress has been

made in fleshing out the details of those settlements, much more

work is needed to get across the finish line.

Babbitt, who was called upon to help

hammer out the voluntary settlement process designed to provide

water users with a soft landing, said while progress has been

made in fleshing out the details of those settlements, much more

work is needed to get across the finish line.

The voluntary settlements center on the idea of functional flow and the implications of matching water flow to habitat in a way that benefits salmon and other fish. Advocates of functional flows say they are superior to what they view as arbitrary unimpaired flows. Functional flows, they say, put every drop to work, including being spread across fields to promote food production for fish and bird habitat.

“We are all struggling with what the meaning of that is for the Delta … but you can reconceptualize the Endangered Species Act,” Babbitt said. “There is space to do these things if people have the creativity and if we quit this state-federal fight and sit down and work at it.”

“If California could come up with a compact, I guarantee you that federal regulation would back off.”

~Bruce Babbitt, former Arizona governor and Secretary of the Interior

Even so, Babbitt said, it’s going to take a little more water to make the Endangered Species Act work.

“Maybe not a vast amount, but that’s the point, understandably, where it gets difficult and we are not there,” he said, adding that “some reduction” in use has to occur on the Sacramento River side. To alleviate that, he suggested that a water diversion fee could be spread among users that could also help fund needed science and compensate those who give up water.

Babbitt said the greatest result of the voluntary settlements discussion is the promotion of talking, listening and understanding.

It was not free of turbulence, however.

“There were a lot of weeks out here when I walked away from those meetings thinking ‘we are getting nowhere’ and that I’m sick and tired of this process and going to hand in my resignation to the governor and never come here again,” he said.

Despite the headaches, Babbitt said he sees value in consensus-driven solutions such as what’s emerging with the voluntary settlement agreements for the State Water Board’s Delta flows plan.

“Keep after the voluntary settlement process,” he urged. “It ain’t perfect, but it’s going to make a real difference on the tributaries.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.