Can a Grand Vision Solve the Colorado River’s Challenges? Or Will Incremental Change Offer Best Hope for Success?

WESTERN WATER IN-DEPTH: With talks looming on a new operating agreement for the river, a debate has emerged over the best approach to address its challenges

The Colorado River is arguably one

of the hardest working rivers on the planet, supplying water to

40 million people and a large agricultural economy in the West.

But it’s under duress from two decades of drought and decisions

made about its management will have exceptional ramifications for

the future, especially as impacts from climate change are felt.

The Colorado River is arguably one

of the hardest working rivers on the planet, supplying water to

40 million people and a large agricultural economy in the West.

But it’s under duress from two decades of drought and decisions

made about its management will have exceptional ramifications for

the future, especially as impacts from climate change are felt.

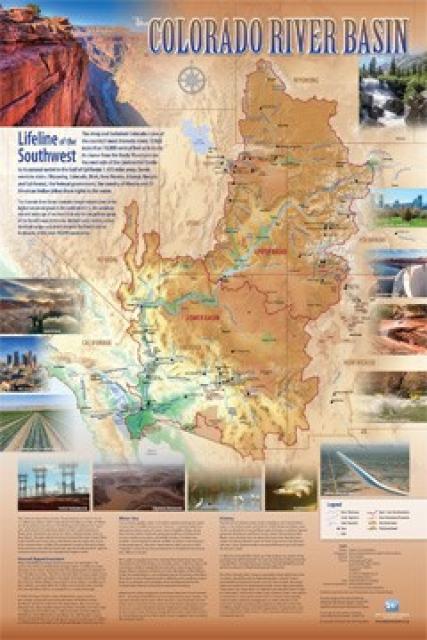

The issues facing water users are many, complex and span the entirety of the 1,450-mile river and its tributaries. The Colorado is overallocated, meaning more water is committed to water users as a whole than is available in an average year. Adding more pressure, the Upper Basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico want to develop their full allocations. American Indian tribes, meanwhile, are asserting their rights to more of the river’s waters.

Amid these challenges, and with critical negotiations looming for an agreement that will chart how the river is operated and managed possibly for decades, a debate is emerging: Should stakeholders pursue a visionary “grand bargain” to wrap their arms around the host of challenges facing the Colorado River? Or is an incremental approach – solving the puzzle piece by piece instead of the whole puzzle at once — the best path toward getting disparate stakeholders to reach a consensus?

The stakes are high. Parties with an

interest in the river will renegotiate the 2007 Interim

Guidelines for shortage sharing and river operations that expire

in 2026. The landmark 2007 deal spelled out Lower Basin shortage

guidelines and rules to store conserved water in Lake Mead and equalize storage in both

Mead and Lake

Powell. Those issues have become even more critical as a

two-decade drought and a structural deficit continue to drop the

level in Lake Mead.

The stakes are high. Parties with an

interest in the river will renegotiate the 2007 Interim

Guidelines for shortage sharing and river operations that expire

in 2026. The landmark 2007 deal spelled out Lower Basin shortage

guidelines and rules to store conserved water in Lake Mead and equalize storage in both

Mead and Lake

Powell. Those issues have become even more critical as a

two-decade drought and a structural deficit continue to drop the

level in Lake Mead.

The debate surfaced anew in September at the Water Education Foundation’s Colorado River Symposium in Santa Fe, N.M. Panelists representing major stakeholders across the basin repeatedly invoked the idea of an incremental vs. a visionary approach as key interests prepare for those guideline negotiations, expected to begin in late 2020.

David Palumbo, the Bureau of Reclamation’s deputy commissioner, challenged the notion of a dividing line between incrementalism and grand visionary, suggesting to symposium participants that the two can coexist and are not mutually exclusive.

“Incrementalism is not small,” he said. “It is visionary and … maybe … we can purge our vernacular from this idea of incrementalism, at least the connotation that it’s small, that it’s not visionary.”

In a region that has seen its share of big projects and prolonged drought, some have said the time is right to take unprecedented problem-solving steps such as reopening the terms of the Colorado River Compact, the landmark 1922 document that divided the river into two basins and apportioned its waters.

Obstacles and Challenges

Since the Compact was signed in 1922 and then ratified by Congress in 1928, Colorado River water users have successfully navigated obstacles by a variety of means. Those include landmark deals for shortage sharing and voluntary use reductions to help protect Lake Mead’s water level and keep it from reaching dead pool – the point at which no water could pass Hoover Dam for downstream water users. Set to expire in 2026, the current operating guidelines for water deliveries and shortage sharing are designed to prevent disputes that could provoke conflict.

There is a sense among some that a big plan is needed for 2026 and beyond.

“We need to be more creative in our work and I think incrementalism should be thrown out of the dictionary and we should all become visionary,” Ted Kowalski, senior program officer with the Walton Family Foundation, said at the symposium. He formerly served as chief of the Interstate, Federal and Water Information Section of the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

Kowalski does not advocate reopening the Compact but believes creativity is needed in all aspects of the river’s operating agreements to support a vision that reconnects it with the Sea of Cortez, such as what occurred through a U.S.-Mexico agreement in 2014.

Advocates of incrementalism say it

makes sense to maintain the course of collaboration and

cooperation, staying within the existing framework of the Law of

the River – the all-encompassing term that describes the

compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, and

contracts and regulatory guidelines that oversee the use and

management of the river among the seven basin states and Mexico.

Advocates of incrementalism say it

makes sense to maintain the course of collaboration and

cooperation, staying within the existing framework of the Law of

the River – the all-encompassing term that describes the

compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, and

contracts and regulatory guidelines that oversee the use and

management of the river among the seven basin states and Mexico.

Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman is no fan of reopening the Colorado River Compact to forge a grand bargain.

“I see all these challenges on the river, but I don’t see a clear or a better outcome for this Basin by assuming that all of these challenges could be easily addressed if we were simply to rip up our founding document, the Compact, and start over,” she said at the symposium.

Former Interior Secretary and Arizona Gov. Bruce Babbitt echoed that sentiment, saying at the symposium that it’s not the time to begin a big negotiation about the Compact prior to 2026.

“I’m not a Compact modifier because every time I read that I say, ‘Man, if you can’t find your way to a consensus past that document, you better go back to school, because there’s all kinds of possibilities out there of reconciling these differences rather than stacking them up and sending out our respective advocates to build anticipatory cases,” he said.

Big River, Big Vision

Much of the discussion about Colorado River water use involves semantics. Can the many agreements enacted through years be categorized as incremental progress or evidence of a grander vision? Or is that characterization even the right way to view all the actions that have built dams and aqueducts, solidified water sharing agreements and provided for environmental needs.

Long-time policy participants say the scale and scope of what’s occurred in the past century has not been done piecemeal.

“The Colorado River Compact was not incremental,” Jim Lochhead, chief executive officer and manager of Denver Water, said at the symposium. “It was based on a huge idea of a major dam on the river and the All-American Canal. And it was premised on a lot of structural development in the Upper Basin.”

On the flip side, he said, there have

been environmental actions — the Endangered Species Act, Clean

Water Act, Wilderness Act and the National Environmental Policy

Act — that created a legacy of stewardship and balance on the

river.

On the flip side, he said, there have

been environmental actions — the Endangered Species Act, Clean

Water Act, Wilderness Act and the National Environmental Policy

Act — that created a legacy of stewardship and balance on the

river.

Babbitt said stakeholders can be locked into a narrow focus on the river and their relationship with it.

“All of us have tended for these vision discussions to be compartmentalized into sort of Lower Basin/Upper Basin, as if there’s kind of a virtual curtain across the basin line in which our best efforts at vision tend to look into our basin,” he said.

Major players “need to be out there in this basin, working the vision not via a negotiation, but by some real outreach to talk about the future,” Babbitt said.

“I don’t think we’re even close to being done with innovation and flexibility.”

Brenda Burman, Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner

One possible element of a bold, visionary approach that has been talked about would remove the Lower Basin’s legal right to “call” for water during dry times that was established by the Compact. Under the Compact, the Upper Basin cannot cause flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75 million acre-feet for any period of 10 consecutive years.

According to a November white paper called “The Risk of Curtailment Under the Colorado River Compact,” a debate has swirled since the drafting of the Compact as to whether this imposes a delivery obligation on the Upper Basin states, or merely a requirement that those states not deplete the flows of the river beyond that amount. That debate has intensified as projections of a drying basin have raised concerns that the water won’t be there to meet the obligation to the Lower Basin.

“A delivery obligation (as opposed to a non-depletion obligation) would mean the Upper Basin must absorb any climate change reductions to the flows in the Colorado River … even if that requires curtailing existing uses,” says the paper, written by Anne Castle, senior fellow with the Getches-Wilkinson Center at the University of Colorado Law School, and John Fleck, director of the University of New Mexico’s Water Resources Program.

Meanwhile, American Indian tribes in

the Colorado River Basin want access to water allocations that

are rightfully theirs, but which have not been developed.

Combined, tribes have rights to more water than some states in

the Basin. That means inclusion, collaboration and cooperation

are crucial.

Meanwhile, American Indian tribes in

the Colorado River Basin want access to water allocations that

are rightfully theirs, but which have not been developed.

Combined, tribes have rights to more water than some states in

the Basin. That means inclusion, collaboration and cooperation

are crucial.

“What I’m advocating for is that the Basin states engage with tribes early on and incorporate them into the decision-making process,” Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis of the Gila River Indian Community said at the symposium. “Especially if tribes can bring something meaningful and innovative to the table to help address the difficult challenges we all face in managing our water resources.”

Looking Ahead to 2026

Because the task of creating a revised framework for the operation of the Colorado River in 2026 is so monumental, leadership from key players is critical, said Michael Cohen, senior researcher with the Pacific Institute, a water think tank that promotes sustainable water policy.

Through the years, Colorado River water users have deployed several tools to hone water use accounting and conducted mutually beneficial interstate sharing agreements, actions that were previously unheard of and far from incremental in nature, he said.

“We need to be more creative in our work and I think incrementalism should be thrown out of the dictionary and we should all become visionary.”

Ted Kowalski, Walton Family Foundation

“There’s been significant changes in the river to date, and we like to call them incremental, and that’s how they’re framed,” Cohen said. “But what we’ve seen is dramatic change.”

The 2007 Interim Guidelines to better coordinate the operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead are an example of the dramatic change that’s enabled users to prevent Lake Mead dropping to levels that crash the system. Forged from long-standing water accounting issues between the Upper and the Lower Basins, including the obligation to meet water deliveries to Mexico, the imbroglio resulted in then-Interior Secretary Gale Norton essentially strong-arming the Basin states to get together and resolve their disputes.

Former Reclamation Commissioner Robert Johnson said at the symposium that Norton warned stakeholders that if they didn’t solve the problem, she would.

“She was basically throwing down the gauntlet, an approach that Bruce Babbitt took frequently when he was secretary,” Johnson said. “That was the start of the 2007 guidelines, and true to form, the Basin states came through. They went far beyond just defining on an interim period. I’m sure that the disagreement over the legal aspects of the delivery to Mexico is still there, but the interim guidelines solved that problem for 20 years by putting operational procedures in place.”

Chuck Cullom, manager of Colorado River programs with the Central Arizona Project, said programs such as the 2007 guidelines, compensated conservation programs and voluntary use reductions demonstrate what can happen within the existing framework of laws and regulations to achieve resiliency.

There is a “false choice” between visionary focus and incrementalism, he said, adding that he describes it as incremental transformation. That transformation is evident in interstate and intrastate agreements in which people invested their time and resources to take concepts from development to implementation.

“It is not possible to understand all of the intended and unintended costs of an incremental transformation without testing it first,” Cullom said. “Metropolitan Water District took that concept in the early 90s to demonstrate that water could be saved in Lake Mead by investing with Palo Verde Irrigation District. There was no clear accounting framework to make all that happen, but they created a pathway for intentionally created surplus to be something that we’re all using on the river today.”

Incremental Progress

The challenges facing Colorado River water users are varied and complicated. The decline of water levels in Lake Mead spurred Basin states to sign on to a Drought Contingency Plan in May after more than five years of discussion. Yet Imperial Irrigation District, the river’s largest water rights holder, walked away from the agreement because it failed to address air and water quality issues of a shrinking Salton Sea.

If the past is a reliable indicator,

the answers going forward will build on the legacy of cooperation

and innovation while steering away from precedent-setting action.

If the past is a reliable indicator,

the answers going forward will build on the legacy of cooperation

and innovation while steering away from precedent-setting action.

“There’s lots of increments that have gotten us to where we are today,” Palumbo with Reclamation said. “And those are visionary actions that were taken. They were visionary at the time and as we reflect on them, they’re visionary today.”

Water providers are “too humble” in describing the collective efforts taken to brace against the conditions caused by drought and an overallocated system, Cullom said. “We talk about increments,” he said. “We need to say these are visionary. The system conservation project (in which agricultural users were compensated for conserving water) is a visionary thing instead of an incremental approach to protecting Lake Mead.”

Reclamation Commissioner Burman said she believes there is much left to be done to solidify river management between the Upper and Lower basins.

“I don’t think we’re even close to being done with innovation and flexibility,” she said. “We have tools we haven’t invented yet and we have so much still to learn and do and cooperate and collaborate on this river.”

Does that mean renegotiating the Colorado River Compact is off the table?

“If you merely asked should we reopen the Compact, perhaps everyone can imagine that outcome would be better for their interest group, but I really question how could it be simultaneously better for all of our interest groups?” Burman said. “Looking for a panacea in that Compact renegotiation is just the wrong investment of time and talent.”

“I suggest that the best way to proceed is to have an articulated visionary goal with specific incremental steps to get there.”

Anne Castle, Getches-Wilkinson Center, University of Colorado Law School

Castle with the University of Colorado Law School said the time is now for communities to bolster themselves against a future supply shock through varying responses, including clarifying shortage sharing rules and setting up voluntary, compensated water conservation programs.

“We think that any of those discussions need to be based on an objective risk assessment that could lead to either incremental or more radical approaches to Colorado River management,” she said in an email, referring to herself and Fleck, her research paper coauthor.

Castle, who served as assistant secretary for water and science at the Department of the Interior in the Obama administration, believes there is a false dichotomy between the incremental and visionary characterization of river management.

“I suggest that the best way to proceed is to have an articulated visionary goal with specific incremental steps to get there,” she wrote. “The vision is needed to guide choices along the way, but it’s not either desirable or realistic to suddenly make big changes in operations on the river, precipitously undermining investments and reliance on the previous status quo.”

Scientists warn that a drying climate means Colorado River flows could diminish substantially in the next 50 years. The prospect of steep declines in flows adds a sense of urgency because of the potential impacts to the environment, cities and agriculture.

“This river can turn on a dime, and

we need to be prepared for it as a Basin,” said Lochhead, with

Denver Water. “If we take too incremental of an approach, we

could be caught short. We need to be aspirational in terms of

what we think we can achieve and reach for that and get as far as

we can in this next set of negotiations.”

“This river can turn on a dime, and

we need to be prepared for it as a Basin,” said Lochhead, with

Denver Water. “If we take too incremental of an approach, we

could be caught short. We need to be aspirational in terms of

what we think we can achieve and reach for that and get as far as

we can in this next set of negotiations.”

Kowalski, with the Walton Family Foundation, urged stakeholders to be innovative and not be afraid to act.

“We need to remember the river in all of this,” he said. “It’s critically important to take care of the river as well as your service requirements. I want to challenge you … as we’re looking at the renegotiations, how do we do that and not just have it be for the benefit of the system but for the benefit of the river that sustains us all?”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Further Reading

- Western Water: Could “Black Swan” Events Spawned by Climate Change Wreak Havoc in the Colorado River Basin? Sept. 12, 2019

- Western Water: With Drought Plan in Place, Colorado River Stakeholders Face Even Tougher Talks Ahead On The River’s Future, May 9, 2019

- Western Water: As Shortages Loom in the Colorado River Basin, Indian Tribes Seek to Secure Their Water Rights, Nov. 2, 2018

- Western Water: Despite Risk of Unprecedented Shortage on the Colorado River, Reclamation Commissioner Sees Room for Optimism, Sept. 21, 2018

- Western Water: New Leader Takes Over as the Upper Colorado River Commission Grapples With Less Water and a Drier Climate, Aug. 10, 2018

- Aquapedia: Colorado River