New Leader Takes Over as the Upper Colorado River Commission Grapples With Less Water and a Drier Climate

WESTERN WATER Q&A: Amy Haas, executive director, Upper Colorado River Commission

Amy Haas recently became the first non-engineer and the first woman to serve as executive director of the Upper Colorado River Commission in its 70-year history, putting her smack in the center of a host of daunting challenges facing the Upper Colorado River Basin.

Amy Haas recently became the first non-engineer and the first woman to serve as executive director of the Upper Colorado River Commission in its 70-year history, putting her smack in the center of a host of daunting challenges facing the Upper Colorado River Basin.

Yet those challenges will be quite familiar to Haas, an attorney who for the past year has served as deputy director and general counsel of the commission. (She replaced longtime Executive Director Don Ostler). She has a long history of working within interstate Colorado River governance, including representing New Mexico as its Upper Colorado River commissioner and playing a central role in the negotiation of the recently signed U.S.-Mexico agreement known as Minute 323.

As executive director of the Upper Colorado River Commission, Haas is likely to play a major role in helping to address changing hydrologic conditions along the Colorado, drought planning and ongoing water conservation efforts, as well as tribal water rights among Native Americans and their impact in the Colorado River Basin.

“I believe [the commission] is a heck of a lot busier now because we are being confronted with fairly dire hydrology and changing conditions that early on we were not aware of.”

~Amy Haas, Executive Director, Upper Colorado River Commission

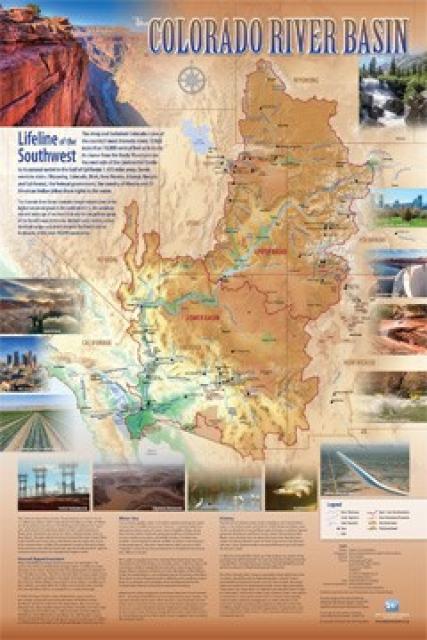

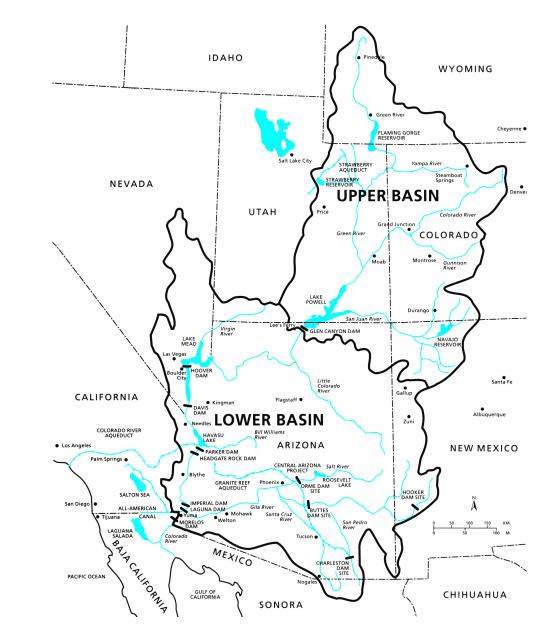

The commission, created by the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact of 1948, is comprised of representatives from Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, all of whom rely extensively on the Colorado River and its tributaries to support important agricultural economies and the demands of a growing urban sector. Among the commission’s duties is a key one: Ensuring the flow of the Colorado River at Lee Ferry, the dividing point between Upper and Lower Basins, does not drop below 75 million acre-feet for any 10 consecutive years as required by the 1922 Colorado River Compact.

That task is challenging because the two basins have many differences, not the least of which is geography. In the Lower Basin, Lake Mead sits above the big cities and farms and is the bank where conserved water is stored. Not so in the Upper Basin where Lake Powell sits below the majority of water users. Conserved water stored in Powell cannot be returned to users in the Upper Basin.

Haas talked with Western Water in July, shortly after she was named to her new position, about the Upper Basin’s challenges, including drought planning, climate change and tribal water rights. The transcript has been edited for space and clarity.

WW: The Upper Colorado River Commission was created 70 years ago. How has its mission evolved since that time and what do you see its role as today?

HAAS: I think fundamentally the role of the commission has evolved in light of the fact we are dealing with hydrologic constraints that are coming to the fore now. This is the first time since the signing of the 1948 Compact that we have had to face the possibility of shortages in the Upper Basin. It’s uncontroverted that temperatures are increasing, and that is leading to diminishment of surface water supplies. We are having to be much more creative in terms of how we manage this resource. I believe [the commission] is a heck of a lot busier now because we are being confronted with fairly dire hydrology and changing conditions that early on we were not aware of. In the early years of the commission, we were operating in the era of big dam construction and surplus water – this is no longer the reality.

HAAS: I think fundamentally the role of the commission has evolved in light of the fact we are dealing with hydrologic constraints that are coming to the fore now. This is the first time since the signing of the 1948 Compact that we have had to face the possibility of shortages in the Upper Basin. It’s uncontroverted that temperatures are increasing, and that is leading to diminishment of surface water supplies. We are having to be much more creative in terms of how we manage this resource. I believe [the commission] is a heck of a lot busier now because we are being confronted with fairly dire hydrology and changing conditions that early on we were not aware of. In the early years of the commission, we were operating in the era of big dam construction and surplus water – this is no longer the reality.

WW: Controversy erupted this year regarding accusations that the Central Arizona Water Conservation District was “gaming” water levels in Lake Mead that would require greater releases out of Lake Powell. (See Western Water, June 15). Do you believe Arizona has responded satisfactorily to the Upper Basin’s concerns? And what happens next?

HAAS: I think Arizona has gotten its intra-Arizona disagreements on track and … has really endeavored to right the ship on the need for a Lower Basin drought contingency plan (DCP). Arizona is first in line to take a shortage and the hydrology seems to be closer in terms of the horizon for a potential shortage as early as 2020.

We are hoping we can keep Arizona engaged. I am optimistic that we will.

WW: The commission opted out of the System Conservation Pilot Program for 2019. Why? Does the program – or some conservation program like it – still have support among Upper Basin ranchers and farmers?

HAAS: For the first three years of the Upper Basin program, we collectively saw a consumptive-use reduction of about 22,000 acre-feet and we spent about $4.5 million doing that. At the end of the day the conservation was substantial, but not in significant enough volumes to really make a dent at Lake Powell.

We demonstrated that the market will support this — people will collaboratively conserve water if they are compensated. Whether we can trace those molecules that are conserved down to Lake Powell — to see if that 22,000 acre-feet actually ended up in Lake Powell — is very difficult to say. These issues were a big part of the commission’s determination to suspend the System Conservation Pilot Program beyond this year.

We demonstrated that the market will support this — people will collaboratively conserve water if they are compensated. Whether we can trace those molecules that are conserved down to Lake Powell — to see if that 22,000 acre-feet actually ended up in Lake Powell — is very difficult to say. These issues were a big part of the commission’s determination to suspend the System Conservation Pilot Program beyond this year.

WW: Is there a chance of some type of conservation program returning?

HAAS: The intent is not to abandon the demand management piece of our drought contingency plan, but rather to look at a more robust demand management program that will help ensure full compliance with the 1922 Colorado River Compact in times of drought.

“Until we have storage, the idea of a bigger system conservation program is an exercise in futility if we have nowhere to keep it.”

~Amy Haas, Executive Director, Upper Colorado River Commission

The other thing that was a big deal for some of the Upper Basin water users that participated was what if we get to a situation [where] we have sent this water to Powell, then we have some bumper hydrology where we really don’t need the water. How can we avail ourselves of this water?

Right now, what we are really focused on is securing new storage for these demand management volumes. Until we have storage, the idea of a bigger system conservation program is an exercise in futility if we have nowhere to keep it.

WW: You were involved with the negotiations that led to the signing of Minute 323. How do you expect that to assist the ongoing drought response/system conservation efforts in the U.S.?

HAAS: Mexico’s participation is key. There is a provision in the Minute that says in addition to the other shortages that Mexico has agreed to take given drier hydrology at various Mead elevations, they’ve also gone over and above by saying they will participate in water scarcity contingency planning reductions. But, they will only go over and above provided the Lower Basin implements a drought contingency plan (DCP). Mexico is playing, and I think that is compelling.

The flip side of that is if we can’t get a DCP together in the Lower Basin, that provision of the Minute doesn’t kick in. …One of the things I am encouraged by is that [Reclamation] Commissioner [Brenda] Burman has been very vocal about her goal of finalizing both the Lower and Upper Basin drought contingency plans by the end of the calendar year. Finalization doesn’t necessarily translate to implementation. We believe strongly that aspects of the Lower Basin DCP need to be subject to federal legislation, so that’s got to happen. There are aspects of our DCP – in particular, the demand management storage piece – that will also need to be legislated. I am encouraged that by the end of the year the negotiations will have successfully concluded, and we’ll have plans that are ready for legislation and subsequent implementation.

The flip side of that is if we can’t get a DCP together in the Lower Basin, that provision of the Minute doesn’t kick in. …One of the things I am encouraged by is that [Reclamation] Commissioner [Brenda] Burman has been very vocal about her goal of finalizing both the Lower and Upper Basin drought contingency plans by the end of the calendar year. Finalization doesn’t necessarily translate to implementation. We believe strongly that aspects of the Lower Basin DCP need to be subject to federal legislation, so that’s got to happen. There are aspects of our DCP – in particular, the demand management storage piece – that will also need to be legislated. I am encouraged that by the end of the year the negotiations will have successfully concluded, and we’ll have plans that are ready for legislation and subsequent implementation.

WW: As the demand for water increases in the Upper Basin, and as the effects of climate change are felt, will there be enough water for everyone? If not, does the Upper Basin have a plan to respond? And do you anticipate further transactions transferring water from ag to urban use?

HAAS: I don’t think DCP gets us to where we need to go. It sets up a framework. The hydrology and the climate change modeling in particular is constantly changing. The numbers we saw coming out of the 2012 Basin Study have vastly changed between then and the recent Udall/Overpeck report. [A 2017 study written by climate scientists Brad Udall with Colorado State University and Jonathan Overpeck (then with the University of Arizona) for the first time linked the Colorado River’s declining flows since 2000 to climate change].

The key to the Upper Basin DCP is drought operations, that is where we really have the most bang for our buck. It allows us to make timed releases and operations at some of the Upper Basin units — Aspinall, Flaming Gorge, Navajo – to send that water to Powell so that we can sustain an elevation and stay out of that very scary minimum power pool elevation that could potentially jeopardize our continued compliance with the 1922 Colorado River Compact. ….

The key to the Upper Basin DCP is drought operations, that is where we really have the most bang for our buck. It allows us to make timed releases and operations at some of the Upper Basin units — Aspinall, Flaming Gorge, Navajo – to send that water to Powell so that we can sustain an elevation and stay out of that very scary minimum power pool elevation that could potentially jeopardize our continued compliance with the 1922 Colorado River Compact. ….

That said, drought operations and drought contingency planning generally are simply temporary fixes. We need to be thinking about more permanent solutions as the actual and forecast conditions continue to worsen, and I believe that opportunity will arise in 2020 when we begin to renegotiate the 2007 interim guidelines. In particular, we need to begin to address the overall supply and demand imbalance that currently exists in the Lower Basin.

WW: What do drought operations look like?

HAAS: At a really basic level, you’ve got these buckets, these reservoirs, and we are trying to come up with a process to enable us to make releases from these reservoirs to Powell in order to increase its elevations when forecasting shows us that we are approaching critical levels at the lake. We would create a drought plan for each reservoir or a combination of reservoirs. It could be one year, it could be multiyear.

In the Upper Basin, drought operations depend on hydrology and creating a process that enables us to respond when and if forecasts tell us we need to. It’s not something we can preordain.

We will make releases downstream in accordance with all the existing environmental compliance for the reservoirs. … then we will do recovery operations to get those volumes back up at a given reservoir or combination of reservoirs, and until that release and recovery is accomplished, we really haven’t completed the drought operations.

We will make releases downstream in accordance with all the existing environmental compliance for the reservoirs. … then we will do recovery operations to get those volumes back up at a given reservoir or combination of reservoirs, and until that release and recovery is accomplished, we really haven’t completed the drought operations.

This will be memorialized in an agreement as part of our DCP package and hopefully be consummated by the end of this calendar year. What we envision is that it will be an agreement between the upper division states through the Upper Colorado River Commission and Secretary of the Interior. We have taken the position in the Upper Basin that we are absolutely operating these drought-response plans consistent with the existing legal authority, but we still may want to have drought operations legislated anyway.

WW: Resolution of tribal water rights claims seems to be a very large variable in the discussion of Colorado River water management. How do you see this matter taking shape and what are the possible ramifications to potential water leases and/or rights transfers?

HAAS: I was involved in implementing the New Mexico Navajo water settlement and we took the position in the state that it is better for us to settle the claim because it does provide certainty with respect to compact compliance. … That’s extremely critical in terms of the management of water in the Upper Basin.

Tribal water rights are a very important matter in the Upper Basin and, as such, we expect the tribes to play an increasingly important role in Colorado River management. The Navajo Nation is the first tribe to participate in the Upper Basin System Conservation Pilot Program and we are hopeful that as conservation programs expand and are developed, we will see participation from additional tribes. We look forward to improving relationships with all of the tribes and to engaging their participation and assistance as we address future challenges on the Colorado River.

Tribal water rights are a very important matter in the Upper Basin and, as such, we expect the tribes to play an increasingly important role in Colorado River management. The Navajo Nation is the first tribe to participate in the Upper Basin System Conservation Pilot Program and we are hopeful that as conservation programs expand and are developed, we will see participation from additional tribes. We look forward to improving relationships with all of the tribes and to engaging their participation and assistance as we address future challenges on the Colorado River.

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

More About the Colorado River

The Water Education Foundation has written extensively about challenges along the Colorado River. These readings may add to your understanding.

Western Water: The Colorado River: Living with Risk, Avoiding Curtailment

Western Water: Two Countries, One River: Crafting a New Agreement

Western Water: Historic Drought and the Colorado River: Today and Tomorrow

Western Water:The Next Steps of the Colorado River Basin Study

River Report: A Warmer Future and Increased Risk

River Report: Keeping System Conservation Going on the Colorado River

River Report: Dealing with Drought in the Upper Colorado River Basin

River Report: Bending the Curve: The Lower Basin Drought Contingency Proposal

River Report: Bigger, Faster Stronger: Climate Change and the Colorado River Basin