Could “Black Swan” Events Spawned by Climate Change Wreak Havoc in the Colorado River Basin?

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: Scientists say a warming planet increases odds of extreme drought and flood; officials say they’re trying to include those possibilities in their plans

The Colorado River Basin’s 20 years

of drought and the dramatic decline in water levels at the

river’s key reservoirs have pressed water managers to adapt to

challenging conditions. But even more extreme — albeit rare —

droughts or floods that could overwhelm water managers may lie

ahead in the Basin as the effects of climate change take hold,

say a group of scientists. They argue that stakeholders who are

preparing to rewrite the operating rules of the river should plan

now for how to handle these so-called “black swan” events so

they’re not blindsided.

The Colorado River Basin’s 20 years

of drought and the dramatic decline in water levels at the

river’s key reservoirs have pressed water managers to adapt to

challenging conditions. But even more extreme — albeit rare —

droughts or floods that could overwhelm water managers may lie

ahead in the Basin as the effects of climate change take hold,

say a group of scientists. They argue that stakeholders who are

preparing to rewrite the operating rules of the river should plan

now for how to handle these so-called “black swan” events so

they’re not blindsided.

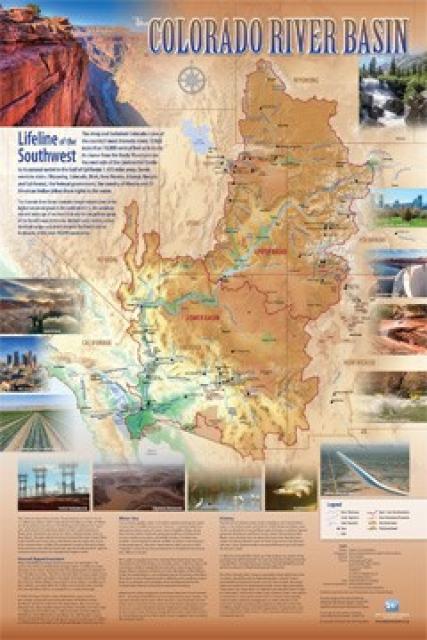

Drought and flood are not uncommon in the volatile Colorado River Basin, which drains 246,000 square miles covering parts of seven states. What’s changed, however, is the variability climate change brings to the Basin’s hydrology.

“There is the sense that we will see things that aren’t in the historical or paleo record and that’s disturbing because it means unprecedented types of events could occur that our systems aren’t designed for,” said Brad Udall, senior research scientist at Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Institute and a member of the Colorado River Research Group, a team of 10 veteran Colorado River scholars.

Udall co-authored the research

group’s May publication,

Thinking About Risk on the Colorado River. It says

an optimum scientific and planning framework is needed to meet

the “black swan.” Failing to account for megadroughts and

catastrophic flooding “is both foolish and unnecessary.”

Udall co-authored the research

group’s May publication,

Thinking About Risk on the Colorado River. It says

an optimum scientific and planning framework is needed to meet

the “black swan.” Failing to account for megadroughts and

catastrophic flooding “is both foolish and unnecessary.”

Colorado River water users by the end of 2020 will begin crucial renegotiations on the 2007 Interim Guidelines for shortage sharing and river operations that expire in 2026. Major water users in the Lower Basin say those new guidelines will include the likelihood of “black swan” events. They believe the past 20 years of adaptive management on the river have them well positioned to bear the brunt of the worst-case scenarios.

“The Colorado River is better prepared than any river in the nation, maybe even the world, because of our storage, for these extreme events,” said Bill Hasencamp, Colorado River Resources Program manager with the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which pulls as much as 1.3 million acre-feet annually from its Colorado River Aqueduct. “If you ever wanted to prepare for megadrought and megaflows, the Colorado is in good shape there.”

“Black Swan” is a term popularized by finance scholar, author and risk analyst Nassim Nicholas Taleb to describe extremely rare but potentially catastrophic events that are beyond the realm of normal expectations.

Chuck Cullom, Colorado River Programs manager with the Central Arizona Project (CAP), which takes 1.5 million acre-feet annually from the river, said his agency prepares for a range of hydrologic scenarios. While unforeseen events have the potential to cause trouble, stakeholders in the Colorado River system are moving toward a more resiliency-based approach in their planning.

Triggers in existing guidelines for

river operations require development of new tools if the risk of

Lake Mead falling below critical elevations increases

dramatically. Meanwhile, CAP is looking at a wider range of water

supply scenarios to facilitate a rapid response to changing

conditions, Cullom said.

Triggers in existing guidelines for

river operations require development of new tools if the risk of

Lake Mead falling below critical elevations increases

dramatically. Meanwhile, CAP is looking at a wider range of water

supply scenarios to facilitate a rapid response to changing

conditions, Cullom said.

The Bureau of Reclamation’s 2012 Colorado River Basin Study said the median of the mean natural flow at Lee Ferry — the dividing point between the Colorado River’s Upper and Lower basins — could decrease by as much as 9 percent during the next 50 years, combined with a projected increase in drought frequency and duration.

Reclamation in 2005-2006 assessed the possibility of Lake Mead reaching critically low elevations through 2026 at about 5 percent. Using more recent information, including climate models, the risk was estimated to be as much as four to five times greater, said Terry Fulp, director of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Region, which oversees water and power operations along the lower Colorado River from Nevada and Arizona to the Mexican border.

“The whole idea of risk in the

easiest form to understand is probability times impact and cost,”

he said. “Low-probability, high-impact events can be relatively

high risk. The best example would be Lake Mead crashing.”

“The whole idea of risk in the

easiest form to understand is probability times impact and cost,”

he said. “Low-probability, high-impact events can be relatively

high risk. The best example would be Lake Mead crashing.”

Water managers for years have dodged and weaved as the Colorado River system has thrown them constant hydrologic curveballs, pushing them to forge new agreements and water conservation measures. Hasencamp, who has served as Metropolitan’s Colorado River manager for 17 years, said the proof of success is that Lake Mead’s water elevation has not dropped to critically low levels that could jeopardize the water supply for more than 23 million people and 2.5 million acres of farmland.

Assessing Risks of Megaflood and Megadrought

Colorado River Basin stakeholders are familiar with drought, having endured a spate of dryness that has rewritten the historic record. Of the 15 driest years in the Upper Basin’s historic record, nine of those years have occurred since 2000, and three of the top five driest have occurred since 2002, according to the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center.

Thinking About Risk notes that it’s unknown whether the current drought could be the beginning of a new megadrought or a result of the aridification trend associated with rising temperatures. Furthermore, there is the risk that natural variability could trigger megadroughts in the future.

“Megadroughts lasting as long as 50 years have occurred in the shared headwaters of the Colorado River and Rio Grande,” according to Udall’s group. “The odds of such extreme drought happening again only go up as the planet warms.”

At the other extreme is flood. In

late spring 1983, an epic-sized flood Udall described as a “black

swan” event roared through the Basin, straining the capacity of

Glen Canyon Dam to convey water fast enough (the force of the

water tore apart portions of the spillway). A repeat of the flood

today would be absorbed by ample reservoir storage space, but the

question of spillway capability remains.

At the other extreme is flood. In

late spring 1983, an epic-sized flood Udall described as a “black

swan” event roared through the Basin, straining the capacity of

Glen Canyon Dam to convey water fast enough (the force of the

water tore apart portions of the spillway). A repeat of the flood

today would be absorbed by ample reservoir storage space, but the

question of spillway capability remains.

Udall pointed to the crisis that occurred in 2017 at Northern California’s Lake Oroville as proof of what can happen in a crunch. At Oroville, pounding flows from a torrential storm damaged the main and emergency spillways, prompting the evacuation of more than 180,000 downstream residents.

“The problem … is those [spillways] need to work perfectly when they are called upon, but they aren’t called upon very often,” he said.

Reclamation has expanded its research capacity regarding climate change and hydrology, but the range of the climate models is wide, Fulp said.

“Some models show no change in precipitation but changes in runoff due to temperature,” he said. “If you just look at the temperature increases and how that maps into what happens with the hydrology on the Colorado River, particularly at Lake Powell, there is a lot uncertainty in it.”

Hard Decisions Ahead

Anticipating “black swan” events requires a sharpened skill set that uses the latest science, Cullom said, adding that better near-term (1 to 5 years) forecasting is needed that incorporates climate signals such as El Niño. Current El Niño forecasting for Colorado River runoff “is only slightly better than using averages,” he said.

Metropolitan’s Hasencamp believes

there is absolutely room for improving forecast data.

Metropolitan’s Hasencamp believes

there is absolutely room for improving forecast data.

“That’s a question I’ve been asking for a long time,” he said. “What’s a good planning model, recognizing the next 20 years is a reasonable time frame for which to plan. What should we assume?”

Udall praised Metropolitan as having “probably the most diversified large-scale water system in the world.” He noted that Las Vegas’ water supply is in better shape after the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s recent $1 billion investment in a third, deeper intake to Lake Mead.

That said, hard decisions await Colorado River Basin stakeholders, including how to address the overallocation of the river’s water in the Lower Basin.

“You’ve got to solve the overuse problem in the Lower Basin and get ready for extended or unprecedented low flows,” Udall said. “We need to look at long-standing assumptions about how the river is managed, including Upper Basin delivery obligations [and] the reality there is not enough water for users in the Upper Basin to continue to export more water to cities like St. George [Utah] and Colorado’s Front Range.”

CAP’s Cullom said management tools

and operating regimes eventually will be tested to assess how

well they address a range of futures including low-probability,

high-impact events. However, until water managers and

stakeholders develop a shared vision of the Colorado River

system, proposing solutions “serves only to advocate for one

approach against another.”

CAP’s Cullom said management tools

and operating regimes eventually will be tested to assess how

well they address a range of futures including low-probability,

high-impact events. However, until water managers and

stakeholders develop a shared vision of the Colorado River

system, proposing solutions “serves only to advocate for one

approach against another.”

Reclamation’s Fulp said the legacy of cooperation and trust in the Basin is important as stakeholders prepare to hash out the details of future river management, including incorporating “black swans.” Reclamation’s Colorado River Basin Research-to-Operations Program is using a variety of scientists on projects that address that very issue.

“We need to continue this research so that our knowledge is always increasing,” Fulp said. “By the time we get to where we are ready to start this renegotiation, we will be smarter than we are today.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Further Reading

- Western Water: With Drought Plan in Place, Colorado River Stakeholders Face Even Tougher Talks Ahead On The River’s Future, May 9, 2019

- Western Water:As Colorado River Stakeholders Draft a Drought Plan, the Margin for Error in Managing Water Supplies Narrows, Dec. 20, 2018

- Western Water: As Shortages Loom in the Colorado River Basin, Indian Tribes Seek to Secure Their Water Rights, Nov. 2, 2018

- Western Water: Despite Risk of Unprecedented Shortage on the Colorado River, Reclamation Commissioner Sees Room for Optimism, Sept. 21, 2018

- Western Water: New Leader Takes Over as the Upper Colorado River Commission Grapples With Less Water and a Drier Climate, Aug. 10, 2018

- Western Water: Historic Drought and the Colorado River: Today and Tomorrow, November/December 2015

- Western Water: A Call to Action? The Colorado River Basin Supply and Demand Study, November/December 2012

- Aquapedia: Colorado River