California Water Agencies Hoped A Deluge Would Recharge Their Aquifers. But When It Came, Some Couldn’t Use It

WESTERN WATER IN-DEPTH: January storms jump-started recharge projects in badly overdrafted San Joaquin Valley, but hurdles with state permits and infrastructure hindered some efforts

It was exactly the sort of deluge

California groundwater agencies have been counting on to

replenish their overworked aquifers.

It was exactly the sort of deluge

California groundwater agencies have been counting on to

replenish their overworked aquifers.

The start of 2023 brought a parade of torrential Pacific storms to bone dry California. Snow piled up across the Sierra Nevada at a near-record pace while runoff from the foothills gushed into the Central Valley, swelling rivers over their banks and filling seasonal creeks for the first time in half a decade.

Suddenly, water managers and farmers toiling in one of the state’s most groundwater-depleted regions had an opportunity to capture stormwater and bank it underground. Enterprising agencies diverted water from rushing rivers and creeks into manmade recharge basins or intentionally flooded orchards and farmland. Others snagged temporary permits from the state to pull from streams they ordinarily couldn’t touch.

Yet not everyone was able to fully capitalize on Mother Nature’s gift.

“When it comes, we have to be prepared to capture as much [water] as possible and put it through our recharge facilities.”

~Kassy Chauhan, executive director of the North Kings Groundwater Sustainability Agency

Drowning land with floodwater to repay groundwater debts requires agencies to navigate a state permitting system that isn’t nimble enough to adapt to sudden changes in weather. Agencies must file complex, costly plans months ahead of California’s notoriously fickle rainy season, a guessing game some didn’t bother with given the likelihood of another dry La Niña winter. And, in some cases, inadequate infrastructure prevented agencies from spreading water to where it was needed while other recharge projects just haven’t moved along fast enough to gulp the deluge.

The barrage of water was in many ways the first real test of groundwater sustainability agencies’ plans to bring their basins into balance, as required by California’s landmark Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). The run of storms revealed an assortment of bright spots and hurdles the state must overcome to fully take advantage of the bounty brought by the next big atmospheric river storm.

“Groundwater recharge is still happening, but we really are still struggling with managing these large volumes of water when they are occurring,” said Helen Dahlke, groundwater hydrologist at the University of California, Davis.

SGMA Success Hinges On Recharge

California in 2014 became the last state in the West to adopt a framework for regulating the use of groundwater, ending decades of largely uncontrolled pumping that caused wells to go dry and land to sink, particularly in the San Joaquin Valley.

Under SGMA, agencies were required to craft plans detailing how they would prevent the overdrafting of their groundwater savings accounts and bring their basins into balance by 2040 or 2042 (depending on the severity of overdraft). The plans are also supposed to avoid “undesirable results” like degraded water quality, land subsidence, stream depletion and harmful effects on drinking water wells. If deadlines aren’t met, the state can intervene and impose an interim management plan for an individual basin.

The dominant strategy of the

sustainability plans, particularly those submitted by agencies

with critically overdrafted basins in the San Joaquin Valley, is

capturing and depositing stormwater underground during wet

winters to use during future dry years. Therefore, the success of

many sustainability plans hinges upon capturing the type of rain

California saw early in the year, said Kassy Chauhan, executive

director of the North Kings Groundwater Sustainability Agency,

which covers the city of Fresno and surrounding areas.

The dominant strategy of the

sustainability plans, particularly those submitted by agencies

with critically overdrafted basins in the San Joaquin Valley, is

capturing and depositing stormwater underground during wet

winters to use during future dry years. Therefore, the success of

many sustainability plans hinges upon capturing the type of rain

California saw early in the year, said Kassy Chauhan, executive

director of the North Kings Groundwater Sustainability Agency,

which covers the city of Fresno and surrounding areas.

“In the post-SGMA world, the importance of [recharge] has become extremely elevated, particularly because you never know when the next wet season is going to come,” said Chauhan. “When it comes, we have to be prepared to capture as much as possible and put it through our recharge facilities.”

The scope of the groundwater problem in the San Joaquin Valley, California’s agricultural heartland, is daunting. Experts estimate the region’s annual groundwater deficit is about 2 million acre-feet – or enough to fill San Luis Reservoir near Los Banos, a key component of two major state and federal water projects.

‘A Wet, Wet Year’

For many basins in the San Joaquin Valley, 2023 has provided the first real dousing since the first batch of sustainability plans was submitted in 2020, allowing agencies to activate their groundwater recharge schemes.

“It’s been a wet, wet year. Some creeks are flowing harder than they did in 2017,” said Jarrett Martin, who helped craft sustainability plans for the critically overdrafted Delta-Mendota Subbasin on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley. “Most folks are looking for opportunities to capture flood flows and recharge.”

Martin said agencies and property owners have been able to steer flood releases from Los Banos Creek Detention Dam into designated prime groundwater recharge areas. Martin’s water district and others have constructed a control structure to move floodwater into the Delta-Mendota Canal as part of multi-benefit project that boosts local water supply, reduces flood risk and protects nearby habitat restoration.

On the east side of the San Joaquin

Valley, the Kings Subbasin, spanning parts of Fresno, Kings and

Tulare counties, has made large recharge basins the center of its

SGMA strategy, perhaps more than any other.

On the east side of the San Joaquin

Valley, the Kings Subbasin, spanning parts of Fresno, Kings and

Tulare counties, has made large recharge basins the center of its

SGMA strategy, perhaps more than any other.

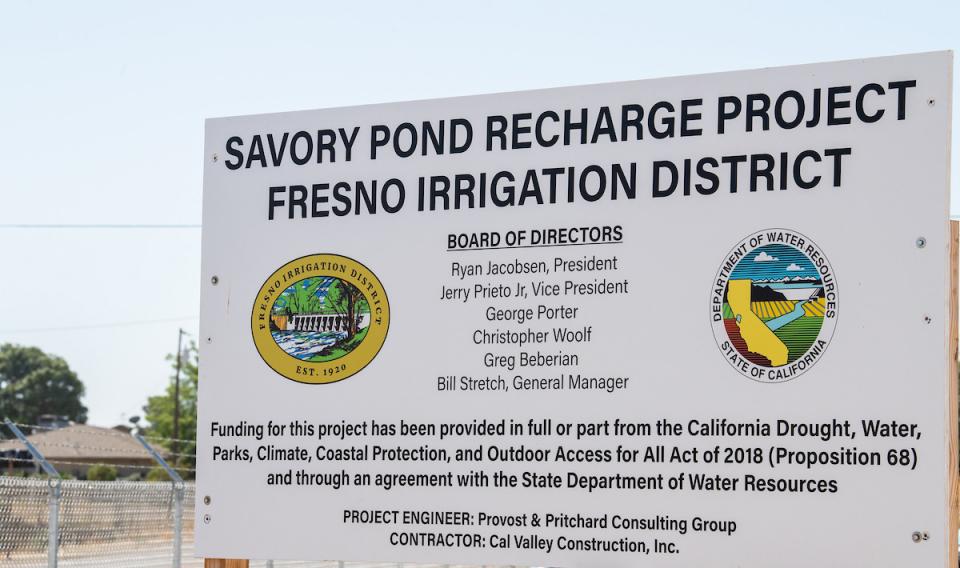

Since 2020, Kings Subbasin agencies have dedicated 1,280 acres of land specifically to groundwater recharge. An assortment of recharge basins are scattered throughout the Fresno metropolitan area and resemble small lakes or ponds. By the time the projects and related infrastructure necessary to fill the basins are completed, Fresno Irrigation District anticipates being able to recharge 25,000 acre-feet per month. For context, the California Aqueduct has a maximum capacity of 26,000 acre-feet per day.

The Kings Subbasin’s long-range planning is reaping rewards in 2023, said Chauhan, who is also the special projects manager for Fresno Irrigation District.

“Had we not had those additional facilities, we wouldn’t have had any place to park the water and it would have been lost to the region,” she said. “To be able to convert those [sustainability] plans into projects that we were able to benefit from is remarkable because it’s hard and challenging.”

Planning recharge basins is easy on paper but executing them is a major undertaking: Agencies often need to negotiate with private sellers to secure land and apply for state grants or other funding to help pay for the project. Recharge basins carry a hefty price tag – the total cost of Fresno Irrigation District’s ponds was approximately $140,000 per acre – and are often tough to sell to ratepayers and board members as they sit dry more often than they are wet.

Fortunately for the district, rising water levels on local creeks and rivers provided ample water for the district’s recharge basins in early 2023. Chauhan said the district has been able to divert flood releases from nearby Friant Dam under a deal with the city of Fresno and bank water that otherwise would have flowed north into the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. It has also made excess water from Pine Flat Dam on the Kings River available for free to growers interested in on-farm aquifer recharge.

Excess Water in Demand

There could be additional recharge opportunities for the Fresno agencies in the near future considering a late-January aerial survey measured 2.3 million acre-feet of snow-water equivalent holding in the mountains above Friant Dam, which can impound a maximum of 520,000 acre-feet of water.

Along with massive recharge ponds, water managers southeast of Fresno in the Kaweah Subbasin are enlisting individual farmers and property owners to expand groundwater recharge on their own land.

Aaron Fukuda, general manager of the Tulare Irrigation District,

said local farmers lined up in droves during the last deluge to

bring in floodwater from the Kaweah River and the Friant-Kern

Canal. He credited the district’s

emergency drought program, which allows farmers to gain credits

for intentionally flooding their land, with creating demand for

the excess water. In previous wet winters, Fukuda said, there was

little interest in flooding farmland, but this time around the

water is seen as precious and necessary to comply with

SGMA.

He credited the district’s

emergency drought program, which allows farmers to gain credits

for intentionally flooding their land, with creating demand for

the excess water. In previous wet winters, Fukuda said, there was

little interest in flooding farmland, but this time around the

water is seen as precious and necessary to comply with

SGMA.

“We’ve always done recharge but now we’re eking out an extra 15-20 percent,” said Fukuda, who is also general manager of the Mid-Kaweah Groundwater Sustainability Agency. “It’s a one-on-one relationship we now have with our growers…now all of a sudden we have 200 recharge agents.”

Stabilizing the water supply for disadvantaged communities is another objective for Tulare Irrigation District. Fukuda said the district has helped communities locate the best areas for recharge as outlined in its sustainability plans.

In coordination with Self-Help Enterprises, a non-profit based in the San Joaquin Valley, Tulare Irrigation District is planning a 20-acre recharge basin that will improve the drinking water supply for the community of Okieville. Residents of the rural town, located in western Tulare County, saw their drinking water wells go dry during the 2012-2016 drought and ultimately received emergency bottled water supplies from the state and Self-Help Enterprises.

“Instead of doing recharge out in the middle of nowhere, we try and focus it around disadvantaged communities,” said Fukuda. “We take some of the excess agriculture supply that we didn’t have a home for and put it beneath the communities.”

A clearer picture of just how much water soaked into the ground from the nine atmospheric rivers that hit California in January won’t be known until the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) issues its spring groundwater level update. The report tracks data that groundwater sustainability agencies are required to submit each spring and fall and helps gauge how much recharge occurred during each rainy season.

Permitting & Planning Hurdles

There was certainly enough water to go around in early January but some willing takers missed out on the floodwaters that raced out of rivers, streams and dams due to red tape.

Most managed or intentional groundwater recharge activities are conducted by parties that already hold existing water rights to a water source. But under California water law, agencies must get permits from the State Water Resources Control Board to capture and later use floodwater from a stream they don’t hold rights to.

These permits allow the agency to maintain control of the diverted floodwater, including the ability to later sell or transfer it; diversions solely for flood control purposes do not require a permit.

“It’s almost like we need a different [permit] application for recharge that is just considered for flood events.”

~Sarah Woolf, farmer and president of Water Wise, a Fresno-area water consulting firm.

But the state’s permitting system isn’t easy to navigate nor is it cheap or timely, critics argue.

“This is exactly the [weather] scenario that most of the [sustainability] plans demonstrate as to how they are going to fix the bulk of the problems,” said Sarah Woolf, farmer and president of Water Wise, a Fresno-area water consulting firm. “Unfortunately, the permitting process is not happening in a streamlined way.”

Woolf, who has helped agencies in Madera and Fresno counties obtain temporary floodwater permits, said farmers or water districts typically hire engineers or lawyers to develop their plans and help conduct environmental studies. They also have to cover application fees that can cost tens of thousands of dollars. Parties that do receive permits then can be required to do things like install fish screens or stream gauges and submit other data to the State Water Board.

There’s also a time element to the process as it can take the State Water Board multiple months to issue a permit because of mandatory public comment periods and consultation meetings. Therefore, agencies must submit their plans well before the rainy season begins. The maze of requirements and uncertainty as to whether floodwaters will even come available often deter agencies from applying to the State Water Board, added Woolf.

“For a small, low-financed water district, it would be very cumbersome,” said Woolf. “It’s almost like we need a different application for recharge that is just considered for flood events.”

Woolf said one of her agricultural water supplier clients currently has a permit to divert floodwater from the Chowchilla Bypass but can’t meet the stringent permit conditions. While some farmers in the Triangle T Water District are taking water out of the bypass, which protects towns in Madera and Merced counties from flooding, they aren’t receiving recharge credits toward their sustainability plans.

“We will not be able to operate under that permit,” she said, adding that only five property owners within the district are diverting floodwater from the bypass under their pre-existing water rights and not the temporary permit.

Pathway to Permits

Amanda Montgomery, permitting program manager for the State Water Board’s Division of Water Rights, countered that the state has made a concerted effort in recent years to streamline the permitting process as well as help fund recharge projects. Since 2015, the state has issued 22 temporary permits, primarily in the San Joaquin River watershed. Of that total, since December 2022 the regulator has issued six temporary permits authorizing more than 174,000-acre feet of diverted floodwater during winter and spring 2023.

Montgomery highlighted two recent temporary floodwater permits that were fast-tracked, including a 180-day permit issued Jan. 6 that allows the Merced Irrigation District and DWR to divert and store water from a local creek. The permit was the first issued through a new state pilot program and authorizes Merced Irrigation District, which co-manages one of California’s 21 critically overdrafted groundwater basins, to take up to 10,000 acre-feet of high-water flows.

Montgomery added that the State Water Board and DWR are seeking to jumpstart similar projects that are focused on taking peak stream flows when there is low risk to fisheries and existing water right holders, like during flooding events.

“It’s important to focus on the fact that there is this pathway out there,” said Montgomery.

Deciding whether to grant a

temporary permit becomes more complicated on streams where most

or all of the water is already appropriated to senior water right

holders or reserved to meet environmental laws, such as the

Tulare Lake Basin. She said the State Water Board worked for

years with the Association of California Water Agencies and

others on determining how high the flows need to be before

issuing permits on an individual river or stream.

Deciding whether to grant a

temporary permit becomes more complicated on streams where most

or all of the water is already appropriated to senior water right

holders or reserved to meet environmental laws, such as the

Tulare Lake Basin. She said the State Water Board worked for

years with the Association of California Water Agencies and

others on determining how high the flows need to be before

issuing permits on an individual river or stream.

“The flows on our streams, a lot of that water is spoken for by senior right holders,” said Montgomery. “The hard part is determining the diversion criteria.”

While UC Davis’ Dahlke credited the State Water Board for trying to improve the permitting process, she said it would be better if it could decouple temporary floodwater permits intended for recharge from traditional surface water rights. She argued the current system is causing missed recharge opportunities and that the processing time for applications needs to be drastically reduced.

“What happened this year is that everyone predicted a dry winter and then all of a sudden we see all of this excess water,” said Dahlke. “So now people are submitting applications that likely won’t get approved until the end of March. By that time, the window might be closing.”

Under SGMA, agencies are required to consider how their sustainability plans will affect groundwater-dependent ecosystems, so many agencies have committed to restoring wetlands or creating recharge basins specifically intended to benefit plants and animals that depend on groundwater for their water needs. Similar to recharge basins designed primarily to boost water supplies, like the ones in the Fresno area, these wildlife-friendly basins require broad-based planning.

Many of these projects are still in the early planning stages and weren’t in position to fully catch water this winter, said Abigail Hart, project director for The Nature Conservancy’s California Water Program.

“A lot of those projects haven’t been developed yet, there hasn’t been enough time,” said Hart, who is helping water agencies in the Tule Subbasin on their sustainability plans.

Hart said there is plenty of enthusiasm for these types of habitat restoration projects in the San Joaquin Valley but that a number of hurdles remain, including land acquisition, permitting and funding.

State’s Recharge Push

To prepare for the types of rain bursts experienced in early 2023 and bolster California’s underground water savings account, Gov. Gavin Newsom has set a goal of expanding groundwater recharge capabilities by 500,000 acre-feet in potential capacity. The State Water Board, DWR and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife are working to reduce red tape and fund the 340 recharge projects proposed under the assortment of sustainability plans.

For example, in 2022 DWR awarded $68

million to 48 different recharge projects across the state and

has received requests for an additional $211 million so far this

year.

For example, in 2022 DWR awarded $68

million to 48 different recharge projects across the state and

has received requests for an additional $211 million so far this

year.

“The state is capturing more water supply by accelerating groundwater recharge permitting and projects that mitigate the impacts of prolonged drought and support long-term sustainable groundwater management,” said DWR Director Karla Nemeth in a statement. “Projects that capture available precipitation, stormwater, or floodwaters to recharge depleted groundwater basins need to be ready to capture high flows when they are available during each wet season, typically October through April in California.”

DWR is also planning to expand Flood-Managed Aquifer Recharge (Flood-MAR), a strategy that involves capturing floodwater and conveying it to floodplains, farmland and wildlife refuges. Since 2021, DWR has been conducting airborne electromagnetic surveys across individual basins to determine areas most compatible with Flood-MAR and other recharge projects. The surveys now cover the entire Central Valley. Newsom has additionally directed DWR to fast-track Flood-MAR-related proposals, as it did with Merced Irrigation District’s recently launched project on Mariposa Creek.

Hicham ElTal, deputy general manager of the Merced Irrigation District, said he hopes the Flood-MAR project will inspire other agencies to take advantage of new state resources that are now available for groundwater recharge efforts.

“The goal is that this effort paves the way for acquiring temporary permits to divert flood flows by groundwater sustainability agencies throughout the state to help groundwater basins reach sustainability,” said ElTal in a statement.

Lessons Learned

The parade of atmospheric river storms that began the new year offered valuable insight into how far California has to go to be able to fully corral bursts of snow and rain.

In addition to a more efficient permitting process for floodwater, UC Davis’ Dahlke said the state should incorporate more nature-based solutions to increase recharge. Strategically pushing back levees and allowing rivers to spread across floodplains can benefit the environment, groundwater tables and reduce flood damage, she said.

Dahlke said the state’s outdated water infrastructure also hinders recharge efforts, noting that most canals were designed to slowly deliver water during the growing season, not distribute floodwater in a managed fashion. Building out conveyance systems to better connect floodwaters to prime recharge areas – the cornerstone of Flood-MAR – will be costly but important.

“Infrastructure is definitely a bottleneck,” said Dahlke.

Martin, who is also general manager of the expansive Central California Irrigation District, which serves water across more than 143,000 acres in western Stanislaus, Merced and Fresno counties, said planning and gaining support for recharge projects is vital during drought years. He hopes the recent storms will serve as a reminder of how flooding farmland can also improve soil quality by flushing salts.

“We need to think 20, 30 or 40 years down the road so we don’t look back and say ‘man, all of our soils are salty and we can’t really grow anything’,” said Martin.

Chauhan with the Fresno Irrigation

District said it was critical to gain early buy-in from

decision-makers and the public on major recharge projects.

Chauhan with the Fresno Irrigation

District said it was critical to gain early buy-in from

decision-makers and the public on major recharge projects.

“You can’t do these projects overnight. You need foresight to buy the property, construct the basins, secure the funding and be ready for the next storm. That process can take one to three years, depending on funding,” said Chauhan.

Montgomery, with the State Water Board, encouraged water agencies to use the state’s resources and submit for temporary floodwater permits well ahead of winter. She added that in addition to the 180-day permit, there is also a five-year option for floodwater recharge now available under a 2020 law that ensures agencies are better situated for future extreme weather events.

The State Water Board issued the first five-year temporary permit on Jan. 11, allowing the Omochumne-Hartnell Water District to divert 2,400 acre-feet from the Cosumnes River in Sacramento County and spread it on dormant vineyards within its service area. As a condition, the district must install fish screens at the two approved diversion sites and paid nearly $10,000 in permit fees. It received 180-day permits in 2021 and 2022 but diverted just 68 acre-feet of floodwater due to low river flows amid the drought.

Restoring groundwater levels is critical to California’s future water supply and there is plenty of space to spread water and let it percolate below ground. The Public Policy Institute of California estimates the state’s 515 groundwater basins collectively can hold at least three times more additional water than California’s existing dams.

Groundwater recharge, whether done naturally or manually, provides a flood of benefits: Farmers get to bank water and flush salts out of their soils, community wells gain a much-needed boost and wetlands fill up to the delight of birds traveling the Pacific Flyway and the benefit of groundwater-dependent ecosystems.

If it wasn’t already clear to California, the recent spate of heavy rain and snow solidified that groundwater recharge is a water supply strategy worth banking on ahead of the next big storm. The San Joaquin Valley’s groundwater agencies are striving to be ready.

Said Tulare Irrigation District’s Fukuda, “We’re stepping it up to the next level.”

Reach Writer Nick Cahill at ncahill@watereducation.org, and Editor Doug Beeman at dbeeman@watereducation.org.

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook , Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.

Further Groundwater Readings from Western Water

- In the Heart of the San Joaquin Valley, Two Groundwater Sustainability Agencies Try to Find Their Balance, Jan. 29, 2021

- With Sustainability Plans Filed, Groundwater Agencies Now Must Figure Out How To Pay For Them, April 10, 2020

- Understanding Streamflow Is Vital to Water Management in California, But Gaps In Data Exist, Oct. 24, 2019

- Recharging Depleted Aquifers No Easy Task, But It’s Key To California’s Water Supply Future, Oct. 10, 2019

- As Deadline Looms for California’s Badly Overdrafted Groundwater Basins, Kern County Seeks a Balance to Keep Farms Thriving, March 28, 2019

- California Leans Heavily on its Groundwater, But Will a Court Decision Tip the Scales Against More Pumping?, Oct. 19, 2018

- Vexed by Salt And Nitrates In Central Valley Groundwater, Regulators Turn To Unusual Coalition For Solutions, July 13, 2018

- Could the Arizona Desert Offer California and the West a Guide to Solving Groundwater Problems?, May 18, 2018

- Novel Effort to Aid Groundwater on California’s Central Coast Could Help Other Depleted Basins, May 4, 2018