Recharging Depleted Aquifers No Easy Task, But It’s Key To California’s Water Supply Future

WESTERN WATER NOTEBOOK: A UC Berkeley symposium explores approaches and challenges to managed aquifer recharge around the West

To survive the next drought and meet

the looming demands of the state’s groundwater sustainability

law, California is going to have to put more water back in the

ground. But as other Western states have found, recharging

overpumped aquifers is no easy task.

To survive the next drought and meet

the looming demands of the state’s groundwater sustainability

law, California is going to have to put more water back in the

ground. But as other Western states have found, recharging

overpumped aquifers is no easy task.

Successfully recharging aquifers could bring multiple benefits for farms and wildlife and help restore the vital interconnection between groundwater and rivers or streams. As local areas around California draft their groundwater sustainability plans, though, landowners in the hardest hit regions of the state know they will have to reduce pumping to address the chronic overdraft in which millions of acre-feet more are withdrawn than are naturally recharged.

It’s not a new problem, but one that is emblematic of California’s long-standing separation of surface water and groundwater in its management oversight. Some say it’s a problem the state should have been working on long ago as other states around the West have done.

“We are so far behind everybody else,” said Felicia Marcus, former chair of the State Water Resources Control Board. “As we get to the point where managed aquifer recharge is the obvious answer to a regular person, a regular person would assume we’re already doing this.”

Marcus was among the panelists from

across the West at a Sept. 10 groundwater recharge symposium

presented by the University

of California, Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy & the

Environment. Panelists discussed a variety of approaches and

challenges to getting water back in the ground to aid depleted

aquifers.

Marcus was among the panelists from

across the West at a Sept. 10 groundwater recharge symposium

presented by the University

of California, Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy & the

Environment. Panelists discussed a variety of approaches and

challenges to getting water back in the ground to aid depleted

aquifers.

Until the passage of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) in 2014, there was no statewide governance regulating groundwater pumping. California was the last state in the West to address its groundwater crisis with regulation.

Landowners could take as much as they wanted, if it was put to a beneficial use. In good times, with stable imported water deliveries and relatively healthy aquifers, pumping is not a problem. But decades of overdraft have put a significant dent in parts of the San Joaquin Valley. The land surface has literally sunk in certain areas because of the large-scale pumping of water. Finally, in 2014, lawmakers sought to put the brakes on the problem with SGMA. Sustainability plans required under SGMA for the most overdrafted areas are due in January 2020.

Heavily opposed during its introduction and still facing resistance today, SGMA emphasizes a ground-up approach that requires local leaders to devise the means to bring the most severely depleted aquifers into balance in the next 20 years.

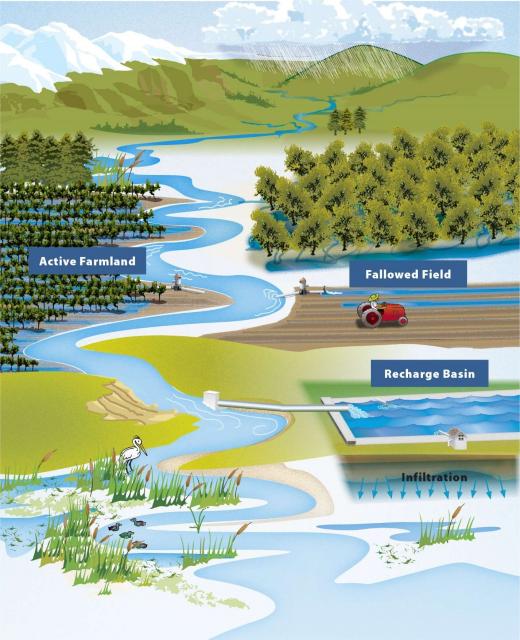

One way to do that is by managed

aquifer recharge, or MAR. Surface water or flows from

storm-swollen rivers are steered onto land where the water

percolates into the ground. It is a straightforward process that

works within the right parameters, experts say.

One way to do that is by managed

aquifer recharge, or MAR. Surface water or flows from

storm-swollen rivers are steered onto land where the water

percolates into the ground. It is a straightforward process that

works within the right parameters, experts say.

“Recharge is just engineering,” Tom Cech, co-director of the One World One Water Center at Metropolitan State University of Denver, said at the symposium. “It’s finding the pipes and a location.”

On average, aquifers provide about 40 percent of the water used by California’s farms and cities in a normal rain year, and significantly more in dry years. There’s a growing recognition that surface water and groundwater are connected: Surface waters gain volume from the inflow of groundwater through the streambed. That volume is lost when groundwater pumping rates exceed natural recharge.

Managed aquifer recharge projects strive to replicate the natural process in which winter rains soak into the ground and replenish water above and below ground. However, projects require extensive monitoring and management to be successful. Farmers for years inadvertently recharged their aquifers through flood irrigation of certain crops and orchards. If they’re asked to act intentionally to recharge, they want assurances they can reap the benefit.

There is “significant potential” to increase MAR on farmland if local agencies adopt better incentive systems and water accounting.

~Public Policy Institute of California

“If we put water in, we want to retain the right to take it out,” Don Cameron, vice president and general manager of Terranova Ranch, 25 miles southwest of Fresno, said at the Berkeley symposium. Terranova has been a leader in using winter runoff to flood its fields for groundwater recharge. “To me that’s the incentive for a grower to do groundwater recharge. I want water security just as much as anyone else does.”

In the West, managed aquifer recharge projects in Colorado, Idaho and Washington state are looking to boost depleted aquifers while at the same time strengthening streamflow and benefiting the environment. “Any time you have more water in the river, it’s good for everyone,” said Jennifer Johnson, hydrologic engineer with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Pacific Northwest Region’s Water Management Group, which is working to replenish aquifers in the Yakima River Valley in south central Washington.

Leaving Water in the Ground

In California, every drop of surface water is accounted for, even the bonus flows that come during very wet years.

In the strict, defined world of the state’s water rights, quantity, beneficial use and avoiding wasteful use is paramount. Beneficial use means exactly that. It’s the water people use at home each day, the irrigation that raises crops and the hydroelectric power so crucial as a renewable energy source.

It’s also the water that pulses through major waterways, keeping fish like salmon alive and healthy as they migrate to and from the ocean.

While helpful, the act of storing

water to recharge aquifers is not a designated beneficial use,

according to the State Water Board. Obtaining a water right to

divert water to underground storage means identifying the

eventual beneficial use of that water, the board says. That could

include uses that allow for water to remain in the aquifer, such

as to prevent land subsidence.

While helpful, the act of storing

water to recharge aquifers is not a designated beneficial use,

according to the State Water Board. Obtaining a water right to

divert water to underground storage means identifying the

eventual beneficial use of that water, the board says. That could

include uses that allow for water to remain in the aquifer, such

as to prevent land subsidence.

That process is not as difficult as it sounds because a wide interpretation exists for beneficial uses, especially as it relates to avoiding some of the undesirable results identified in SGMA.

Managed aquifer recharge and groundwater banking are essentially the same practice with different outcomes. Managed aquifer recharge boosts overall health of aquifers and nearby rivers and streams. In some instances, some of the water can be pumped back up. In groundwater banking, water is intentionally injected or percolated strictly for later withdrawal. Groundwater banks such as those in the southern San Joaquin Valley store vast quantities of imported water that faraway partners use through a complicated exchange process.

The key is having the available water to get into the ground — not always an easy task. “We’ve had two very wet years recently, but in most years, we don’t really have excess surface flows that can be recharged to groundwater, at least not in significant amounts,” said Dave Owen, professor at UC Hastings College of the Law. “And even when we do have flood flows, they aren’t always in the places that most need” the water.

Incremental Implementation – Colorado and Idaho

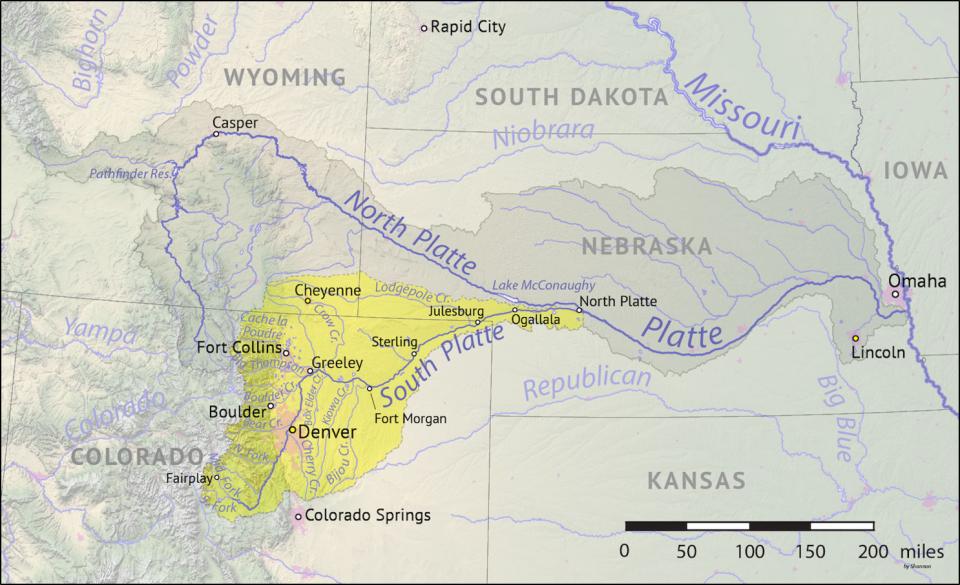

Managed aquifer recharge is

instrumental in preserving the health of the South Platte River

in northeastern Colorado, where groundwater pumping has been

depleting flows in the river. There, well owners have been paying

taxes and annual assessments since 1973, in part to construct

groundwater recharge sites.

Managed aquifer recharge is

instrumental in preserving the health of the South Platte River

in northeastern Colorado, where groundwater pumping has been

depleting flows in the river. There, well owners have been paying

taxes and annual assessments since 1973, in part to construct

groundwater recharge sites.

In 2006, due to a drought and changing legal parameters, the annual assessments were increased 400 percent and about $100 million of bonds have been approved since then by voters. Some of those funds were used to construct recharge projects, said Cech with Metropolitan State University in Denver.

In Idaho, about a third of the state’s economy relies on the agricultural products from the region known as the Eastern Snake River Plain Aquifer in southern Idaho. A decade ago, with the water table dropping, lawmakers saw the coming crisis and adopted a comprehensive water management plan for the area.

Idaho decided to tackle managed aquifer recharge from a state perspective because of the scale of the project (10,000 square miles), the aversion to a new tax and the realization that the cost of doing nothing was not acceptable.

~Wesley Hipke, recharge program manager with the Idaho Department of Water Resources

“The declining spring river flows as a result of the declining aquifer would have resulted in curtailing most of the groundwater users in the area,” said Wesley Hipke, recharge program manager with the Idaho Department of Water Resources. “This would not only have affected agriculture, but also the cities and towns and related industries that are currently in place.”

Idaho decided to tackle managed aquifer recharge from a state perspective because of the scale of the project (10,000 square miles), the aversion to a new tax and the realization that the cost of doing nothing was not acceptable, Hipke said.

“Obviously without a stable water supply, the prospect of future growth is slim,” he said.

The state’s plan outlined the means to manage overall water demand while increasing aquifer recharge and reducing withdrawals. Grabbing as much natural flow as possible, the plan’s aim is to reach 250,000 acre-feet of annual recharge by 2024.

Challenges and Potential for MAR in California

As vital as groundwater is to

California’s water supply, the extent of expanded managed aquifer

recharge remains to be seen. Aquifers are recharged naturally

every time it rains and snows, but carefully managed recharge is

happening on a limited basis.

As vital as groundwater is to

California’s water supply, the extent of expanded managed aquifer

recharge remains to be seen. Aquifers are recharged naturally

every time it rains and snows, but carefully managed recharge is

happening on a limited basis.

“There’s no question it can expand. The question is by how much,” said Owen with UC Hastings.

In its review of groundwater recharge, the Public Policy Institute of California noted in September that a key challenge is inadequate conveyance for moving storm flows to suitable recharge locations. There is “significant potential” to increase MAR on farmland if local agencies adopt better incentive systems and water accounting, PPIC wrote.

Getting water in and out of aquifers using MAR is a big challenge, from an infrastructure standpoint of getting the water when it’s available and moving it to where it can sink into the ground, Owen said in an interview. In addition, there’s not a perfect accounting process for tracking those water molecules. Even in cases where groundwater is being banked, getting the water back out that someone has put in can be complicated in aquifers with “unrestrained, poorly regulated” pumping.

“If you put water into a bank, you may have a legal right to withdraw it,” Owen said, “but that legal right does you no good if someone else has pumped out the physical water.”

Reach Gary Pitzer: gpitzer@watereducation.org, Twitter: @gary_wef

Know someone else who wants to stay connected with water in the West? Encourage them to sign up for Western Water, and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Further Reading

- Western Water: As Deadline Looms for California’s Badly Overdrafted Groundwater Basins, Kern County Seeks a Balance to Keep Farms Thriving, March 28, 2019

- Western Water: Imported Water Built Southern California; Now Santa Monica Aims To Wean Itself Off That Supply, Feb. 28, 2019

- Western Water: California Leans Heavily on its Groundwater, But Will a Court Decision Tip the Scales Against More Pumping? Oct. 19, 2018

- Western Water: Novel Effort to Aid Groundwater on California’s Central Coast Could Help Other Depleted Basins, May 4, 2018